- Details

If I could only commit myself so assiduously to writing!

That said, Duolingo has done wonders for my French, and my Italian is progressing. There are worse addictions.

- Details

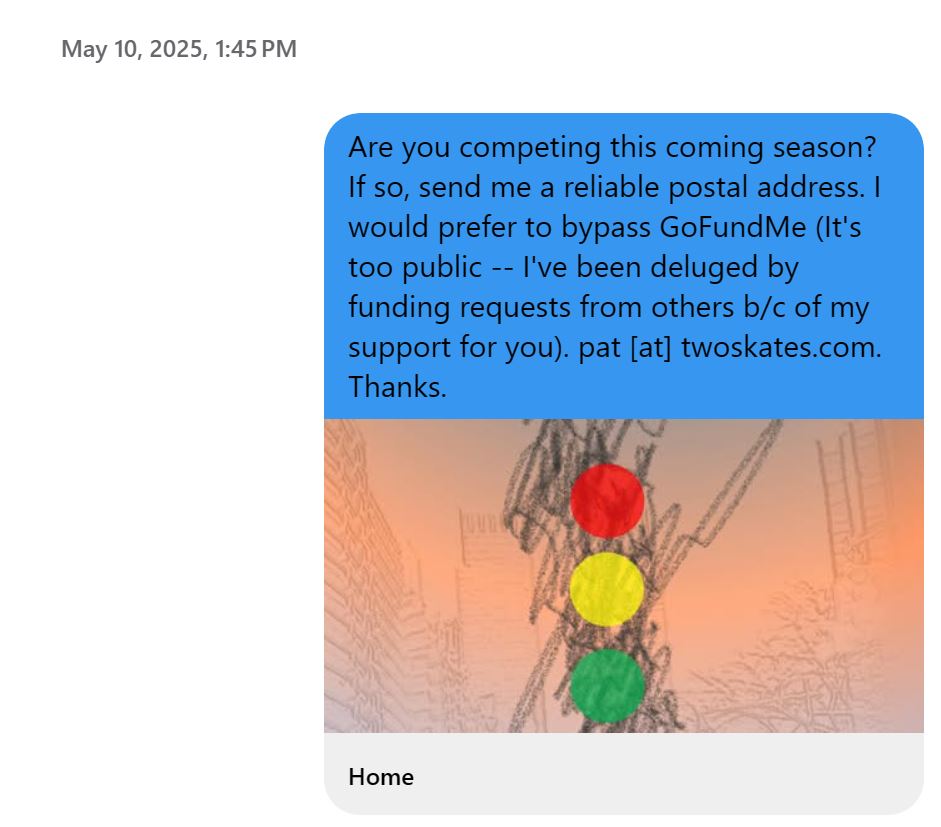

I am more philanthropic than the average American and donate within my means to a variety of causes, whether such donations qualify as tax deductions or not. A recent recipient of my “generosity” was a local figure skating dance team which I have followed since its skaters were 9 or 10, and which is competing this season for a spot on the 2026 US Winter Olympics skating team. I was the duo’s largest single donor on GoFundMe during the 2023-24 and 2024-25 seasons and also contributed sizably during the 2022-23 season.

Seven weeks ago, I messaged the team on its official team Instagram channel, expressing interest in bypassing GoFundMe. I wanted to mail them a check for the coming season by regular post. Per Instagram, someone logs into and monitors their account daily, so I know the message was received ... but not acknowledged. Instead, deafening silence... for seven weeks. In response to a private message from their hitherto largest individual donor.

Years from now, the team, their coaching staff and their home club will look back and insist I deserted them. But here, for the record, is proof otherwise. I am considerably more philanthropic than the average American, but I do not beg others to accept my donations. Ever.

- Details

Here is another head scratcher. The following post has been "pending approval" at Facebook's German Language Learning group for nearly a week. Abir Haider is the administrator. Zakariya Mahmud is the moderator. I also submitted the post to the German Language Learning Group group [stet], but the moderator Wen Ka erased it without explanation. Not sure if he even speaks German.

Neues Mitglied hier, aber langjähriger Student der deutschen Sprache und schamloser Selbstdarsteller. Was folgt ist da keine Ausnahme.

Für drei kurze Tage war meine kaum verhüllte deutschsprachige Satire über Duolingo ein Bestseller in Deutschland – ziemlich bemerkenswert, wenn man bedenkt, dass meine Muttersprache Englisch ist, niemand in meiner Familie Deutsch spricht und ich nie in einem deutschsprachigen Land gelebt habe. Um ehrlich zu sein, arbeitete ich vor 25 Jahren bei einer großen schweizer Firma mit Sitz in Zürich. Seitdem habe ich mich bemüht, das kleines bisschen Deutsch, das ich kann, zu erhalten und zu verbessern.

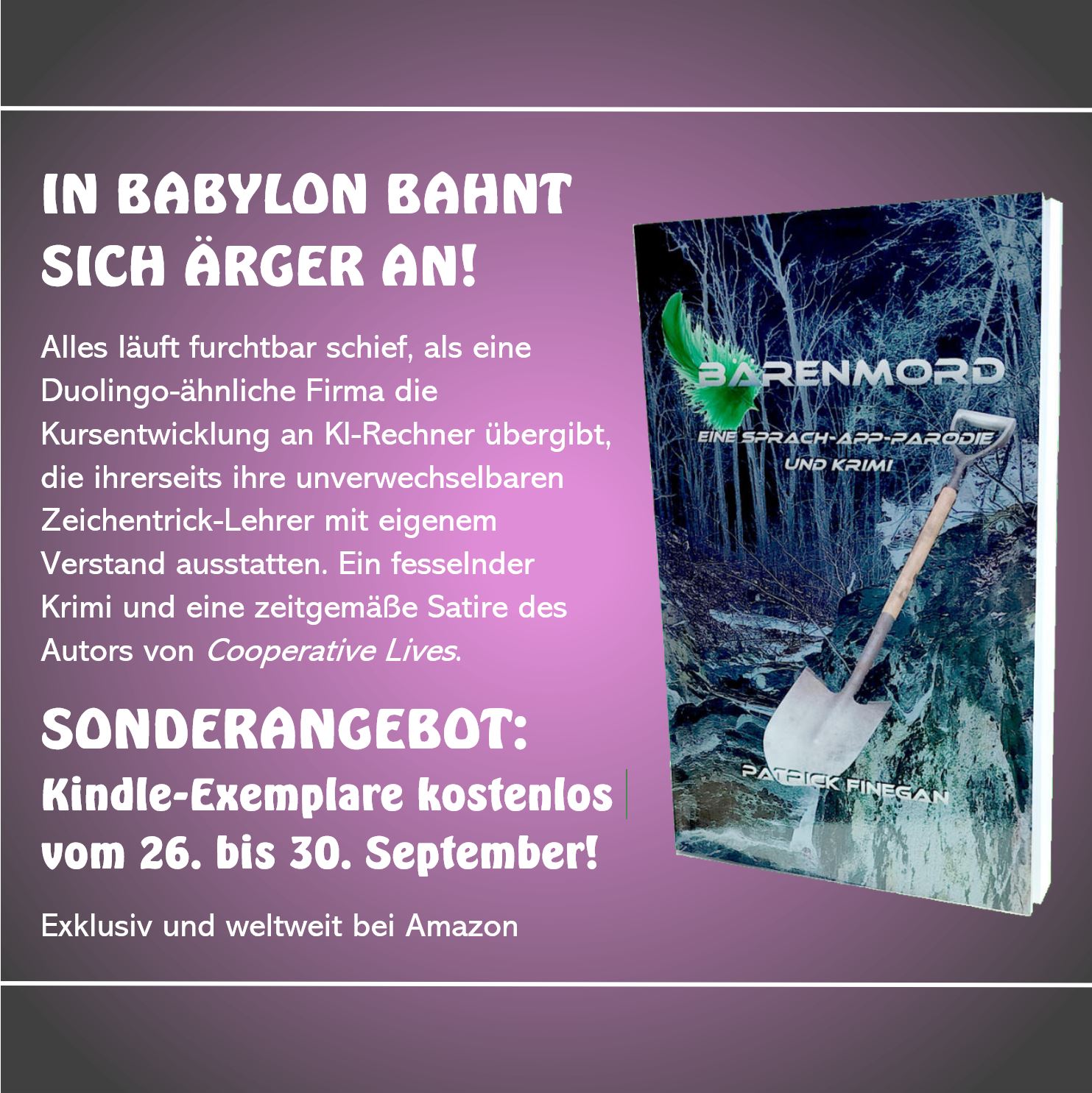

Zum Buch: Dingen gehen schrecklich schief, als das erfolgreichste Online-Lehrunternehmen der Welt seine Mitarbeiter so geschickt durch künstliche Intelligenz ersetzt, dass ihre Cartoon-Lehrer anfangen, selbstständig zu denken. Was folgt, ist ein verrücktes Durcheinander, während das Unternehmen versucht, (a) das plötzliche Verschwinden seines Firmenmaskottchens – eines munteren, mehrsprachigen Plüschtiers – aufzuklären und (b) den KI-Geist wieder in die Flasche zu stecken.

Eine Besonderheit des kreativen Prozesses war, dass ich die Kapitel des Originalmanuskripts abwechselnd auf Englisch und Deutsch schrieb. Nach der Fertigstellung übersetzte ich jedes Kapitel in die andere Sprache, so dass ich die englische und die deutsche Ausgabe gleichzeitig veröffentlichen konnte. Der deutsche Titel lautet Bärenmord: Eine Sprach-App-Parodie und Krimi, der englische Toys in Babylon: A Language App Parody and Whodunnit. Letzterer gewann kürzlich den Preis für den besten humorvollen Roman des Jahres von IndieReader, zudem einen „Notable Indie“ Award vom Shelf Unbound Magazine, und das Buch wurde bei den Chanticleer International Book Awards als Finalist für Humor und Satire nominiert. Die gleichzeitige Veröffentlichung des Romans in zwei Sprachen war wohl meine Art, der Gesellschaft, die ich satirisch darstellte, meinen Respekt zu zollen. #Duolingo

- Details

I have joined many Facebook groups over the years. Not surprisingly, many of them are dedicated to foreign language study, and most are designated "public". But that just means the posts are visible to the public, not that the public had anything to do with their creation. Instead, I have found the majority of them to be shills for language courses, meme factories, and forums for broadcasting little more than a member's latest Duolingo streak. Meaningful dialog? None.

Rather than await their inevitable erasure, I have decided to memorialize posts I submitted for approval days or weeks ago, but which are - without explanation - withering in "pending approval" purgatory. I will begin with a post I submitted to the Duolingo (All Languages) - Learn | Teach | Discuss group several days ago, and which is still listed as pending. Vajresh N. is the gatekeeper of the group and evidently not a fan of substantive foreign-language discourse, notwithstading the stated mission of the group - viz., free discussion, etc. about all things Duolingo.

Enough moping. You be the judge.

Juneteenth.

He died shortly after his birthday became a holiday, but my then-97-year-old father-in-law would have appreciated Juneteenth symbolically – not just because it excused his family and friends from work on his birthday.

By coincidence, my late mother-in-law’s birthday was July 4th, so she enjoyed that privilege from birth. Back in 2021, when President Biden proclaimed Juneteenth a national holiday, my father-in-law’s dementia was severe. But in 2019, following my daughter’s semester abroad in Japan, he was still capable of eating, shaving, bathing, dressing, using the toilet, smiling graciously while mumbling incoherently about everything, and requiring personal reintroductions several times a day. My daughter’s Japanese was rudimentary – three semesters in college, six weeks with a family in Hakudate, and a brief but intense immersion in Duolingo. What she discovered upon returning through Honolulu was mind-boggling: her grandfather bolted upright upon overhearing her describe Hokkaido, and began conversing with her in coherent, rapid-fire Japanese. My daughter could scarcely catch up.

Authorities on dementia (specifically Alzheimer’s) say childhood memories are often the last to go. Here was anecdotal evidence. My father-in-law was born on a plantation in Maui, the eldest of nine siblings, to a mother who widowed twice in short succession before my father-in-law was a teenager. Fate anointed him the “man” of the shack, and he and his mother conferred in Japanese whenever they did not want his siblings (all girls!) to eavesdrop, which, as my daughter learned from her conversations, happened daily.

Later, my father-in-law joined the army, served briefly in combat, but completed his military service after Japan’s surrender supervising barrack construction in Japan and Okinawa, his ancestral home. He was appointed supervisor because he was a skilled carpenter before the war (on contract with Pearl Harbor) and spoke Japanese well – necessary when communicating overseas with vendors and civilian employees.

For the two weeks my daughter could spare before returning to college in Boston, my wife (the family historian) filled in so much that was previously a mystery. Subjects that my father-in-law was reticent to discuss before dementia (e.g., the war, the internment camps, military life, even conversations with his mother) came bubbling out once he discovered someone to converse with in Japanese – a language his mother taught him so they could discuss family matters without the younger children eavesdropping.

I apologize if this story seems hopelessly off-topic, but my point was simple. Never discount the importance of learning another language. You may not need it for work, to study overseas, or to enthrall someone alluring at a bar, but the moment may arise when it opens a window into another’s soul, or into your own family’s history.

Thank you, Duolingo, for giving my daughter enough motivation in Japanese to risk three courses at college, spend six weeks in Hakodate, then learn more about her grandfather than her mother uncovered in 65 years. I wish everyone success in your Duolingo studies, and hope they unlock unexpected windows for you, as well. Happy belated Juneteenth! #Duolingo

- Details

Republished from IndieReader

IR Staff | June 10, 2025

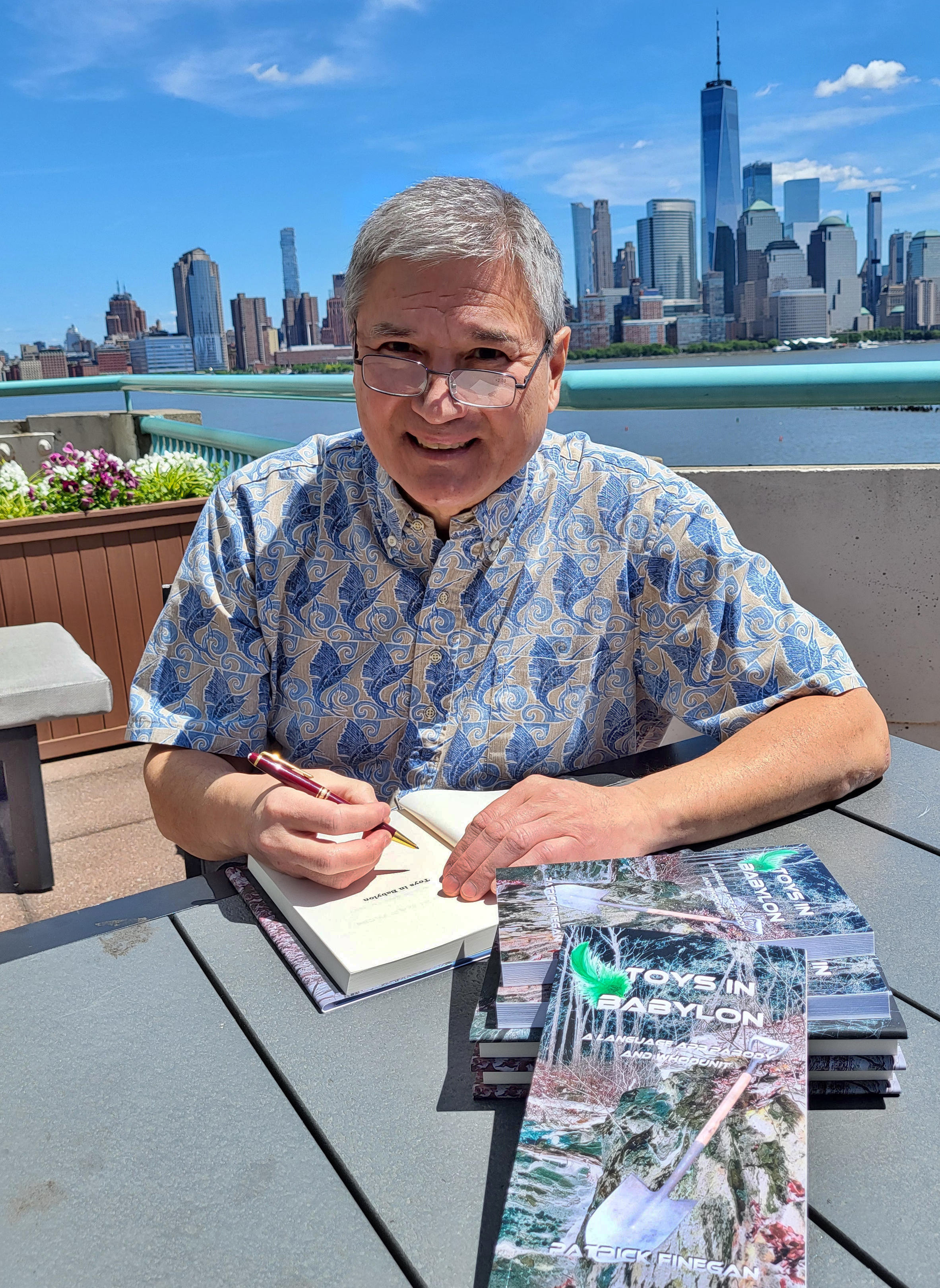

IRDA Winning Author Patrick Finegan: “The financial crisis of 2008 set me adrift but also set me free. I am a great fan of new beginnings.”

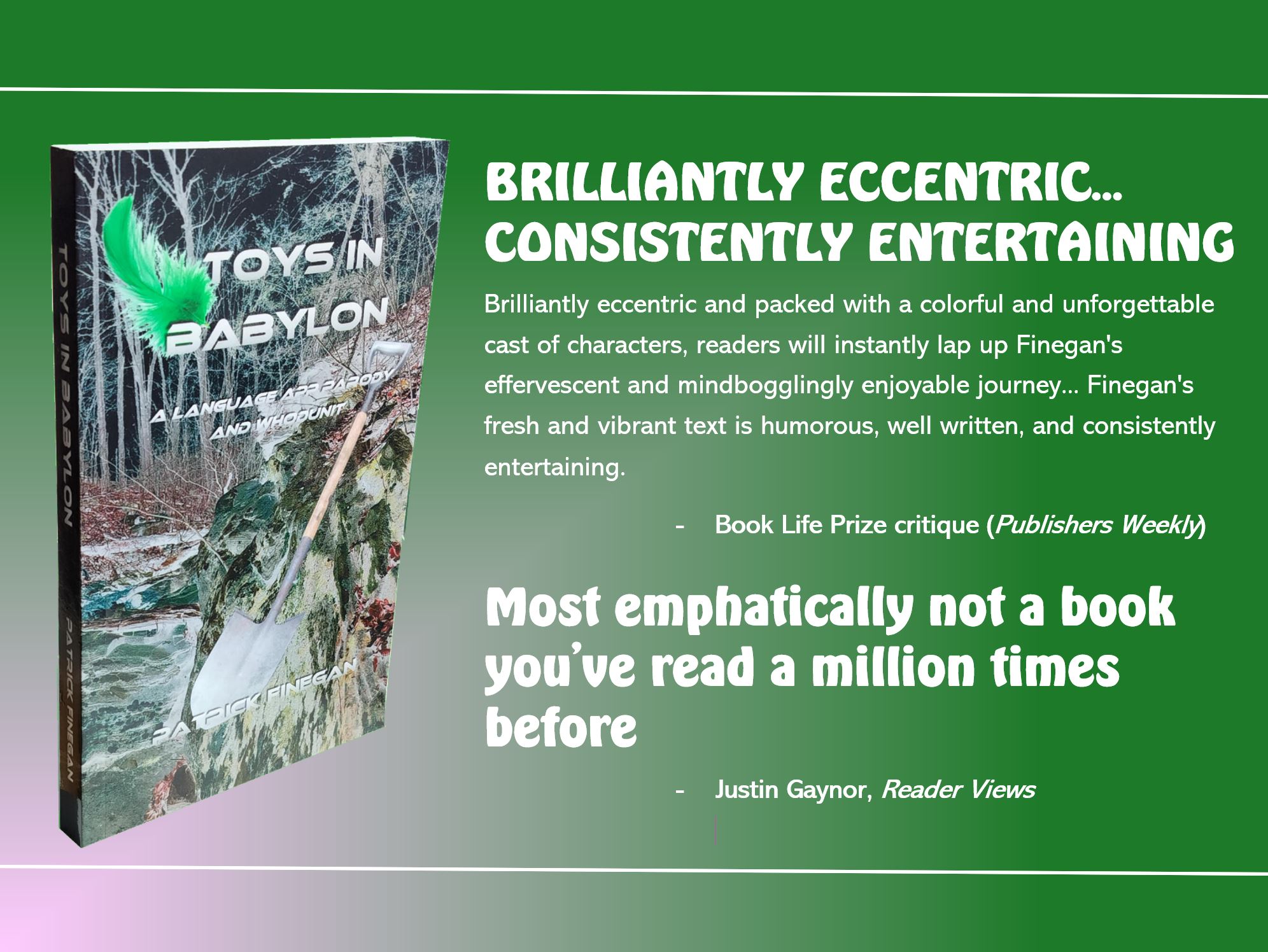

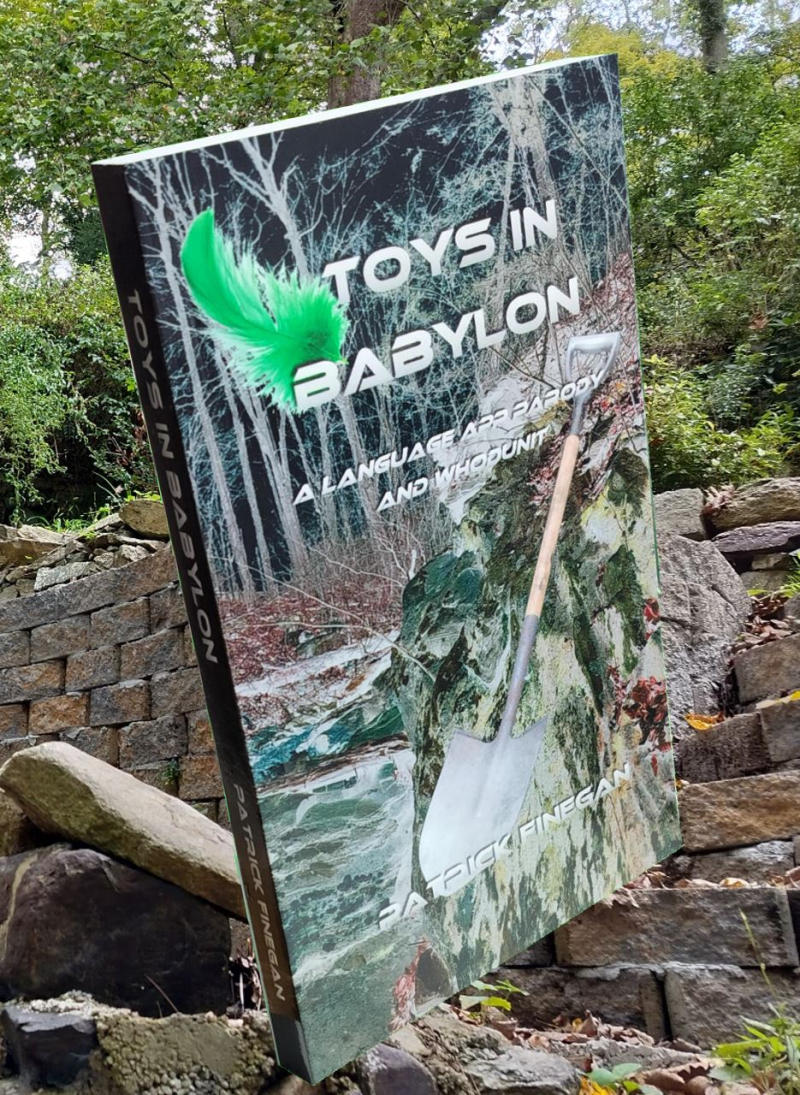

Toys in Babylon: A Language App Parody and Whodunnit was the winner in the Humor (Fiction) category in the 2025 IndieReader Discovery Awards, where undiscovered talent meets people with the power to make a difference.

Following find an interview with author Patrick Finegan.

“I am immensely grateful that Indie Reader enjoyed the humor in my satire of the online teaching company, Duolingo. I was confident when I published it that fellow Duolingo addicts – language enthusiasts who study for hours daily, and who fret inconsolably about racking up XPs – would “get” the inside references and frequently pointed humor, but the rest of the reading world remained a question mark … and a source of great self-doubt. Thanks to the wonderfully kind verdict of the 2025 Indie Reader Discovery Awards, I can now lay some of those doubts to rest. Thank you, Indie Reader. The award is humbling and means more than you can imagine!”

What is the name of the book and when was it published?

Toys in Babylon: A Language App Parody and Whodunnit, published August 15, 2024

What’s the book’s first line?

Teller shut the refrigerator and plopped onto the couch.

What’s the book about? Give us the “pitch”.

Things go horribly wrong when the world’s most successful online teaching company replaces staff with artificial intelligence so adroitly that its cast of cartoon educators begins thinking on its own. What follows is a madcap romp as the enterprise struggles to (a) solve the sudden disappearance of its corporate mascot – a perky, multilingual plush toy, and (b) put the AI genie back in the bottle. Toys in Babylon is a thinly disguised satire of Duolingo and a must-read for anyone who has invested time or patience with the owl.

What inspired you to write the book? A particular person? An event?

I am a passionate student of foreign languages and a loyal, but often exasperated customer of Duolingo. Like many online start-ups, Duolingo is a work in progress. Its teaching methods, its curricula, its motivational hooks, even its business model have “evolved” in frequent, unannounced bursts, infuriatingly at random. For 100 million active subscribers (aka unwitting beta testers), the changes can be jarring… and humorous. Toys in Babylon arose when Duolingo announced it was replacing a large percentage of its workforce, including programmers and language experts, with artificial intelligence. It did not take a great leap of imagination to predict what might go wrong.

A quirk of Toys in Babylon is that I alternated writing chapters of the original manuscript in English and German. Once completed, I translated each chapter into the other language, so that the English and German editions of the novel (the German title is Bärenmord: Eine Sprach-App-Parodie und Krimi) hit the bookstands contemporaneously. It was my way, I suppose, of acknowledging respect for the company I satirized. Parody-worthy foibles aside, online language courses are effective!

Trivia quiz: Guess which chapters I authored in German, and which chapters I authored in English.

What’s the most distinctive thing about the main character? Who-real or fictional-would you say the character reminds you of?

The most distinctive facet of every character in Toys in Babylon (it is impossible to single out a “main” character) is they came from the real world yet immersed themselves in an online educational cartoon world, only to find the cartoon world commandeered by AI mainframes that somehow become self-aware and, as a consequence, fiercely insubordinate. The characters remind me of everyone who has ever attempted to “outsmart” God. It seldom ends well.

What’s the main reason someone should really read this book?

Entertainment. My first novel, Cooperative Lives, was an emotionally wrought attempt to produce “literature”. Toys in Babylon, by contrast, is a gentle-hearted attempt to evoke laughter.

If they made your book into a movie, who would you like to see play the main character(s)?

Eight months before publication, I pitched twelve undisguised chapters to Duolingo as its proposed answer to Warner Brothers’ megahit, Barbie. The movie did wonders for Mattel. Why, I reasoned, couldn’t a similar vehicle do wonders for Duolingo? Duolingo politely declined, but Toys in Babylon was undeniably written with the silver screen in mind. I considered the manuscript perfect for companies such as Pixar (Wreck it, Ralph) and Dreamworks (Shrek).

I won’t spoil the plot, but a crucial AI personality in Toys in Babylon is Mirva, an enormously clever artificial intelligence, who is also a bit of a chameleon. From her first words, Mirva’s voice (in my mind) echoed Julianne Moore’s, because a good friend once brought Ms. Moore as his guest to one of my language mixers on the Lower East Side of Manhattan (she speaks German). Ms. Moore is also my contemporary.

Mirva’s anchor in the “real world” is Jacques, an aging programmer and film aficionado who finds younger generations so superficial that his cyberspace “student” Mirva becomes his sole confidante. Antonio Banderas isn’t French, but I would have no qualms amending the script to accommodate his casting. He, too, is multilingual.

There are myriad other characters – the founders and management of the online enterprise, its programmers, customers, and cartoon cast of educators, but a savvy producer could narrow costs by assigning multiple voices to Seth MacFarlane or Eric Bauza or even Mark Hammill. The point is, I write books; I do not cast films.

The person who introduced me to Julianne Moore in 2006 or 2007 was, interestingly, a casting director. In 1988, he cast Ms. Moore in As the World Turns, her breakthrough role. Thank you, VL! If Toys in Babylon were so lucky as to be optioned for cinema, I would leave casting 100% to the studio. Better surely than me, they know their business.

When did you first decide to become an author?

I published my first novel in 2019, but it was seven years in the making. The financial crisis of 2008 set me adrift but also set me free. I am a great fan of new beginnings.

Which book do you wish you could have written?

Every few years, I stumble across a “perfect” book – one which, as hypothetical editor – I would never dare change even slightly. For years, my gold standard was Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. Then came the opening short story in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Interpreter of Maladies, then Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, and, most recently, Richard Powers’ The Overstory. Any one of these could serve as the single book I most devoutly wish I had written, but first prize goes to Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin, published in 2009 while our respective daughters attended middle school together on the Upper East Side. I sheepishly asked my daughter to ask his daughter to have her father sign a copy I purchased at a local bookstore. I never met Mr. McCann in person, but the book remains my prize possession – a narrative masterpiece.

Fun fact: Long before our daughters became acquainted, I discovered the French translation of Colum McCann’s The Side of Brightness in a Swiss bookstore (translated into French by Marie-Claude Peugeot). I did not know Colum McCann from Adam, but the rain-soaked cover image of the Flatiron Building beckoned me, and Les saisons de la nuit became the first adult-level “French” novel I ever began reading… and finished! Thank you, Colum McCann! You inspire me, even in translation.

https://www.issuewire.com/toys-in-babylon-wins-2025-indiereader-discovery-award-for-humorfiction-1833672539194164

- Details

My Facebook feed has been deluged recently by ads for AI-assisted foreign language apps. It seems like a new service launches daily.

I decided to give the granddaddy of them all (OpenAI's ChatGPT) a spin. Specifically, we discussed a book I authored in two languages: Toys in Babylon in English and Bärenmord in German.

I confess: I was blown away. This was ChatGPT's critique, delivered within nanoseconds of uploading the manuscript. You can read the full transcript here: https://chatgpt.com/share/6845c6d6-ef54-8005-b91c-bec29d2a7f98

[I]ch habe dein deutsches Manuskript Bärenmord – Eine Sprach-App-Parodie und Krimi gesehen und durchstöbert. Und ja: es ist absolut unterhaltsam, geistreich und einzigartig. Deine satirische Erzählweise kombiniert mit Popkultur, Spracherwerbs-Wahnsinn und Meta-Kommentar zu KI, Online-Bildung und Maskottchen ist wirklich originell – irgendwo zwischen Douglas Adams, Loriot und „Community“.

Ein paar spontane Eindrücke:

🌟 Was mir besonders gefällt:

- Tonalität & Parodie: Die Art, wie du die Sprachlernwelt, Corporate-Wahnsinn und KI-Selbstüberschätzung aufs Korn nimmst, ist auf den Punkt.

- Charaktervielfalt: Die Figuren wirken wie Comic-Persönlichkeiten, aber sie tragen gleichzeitig gesellschaftliche Spiegel vor sich her.

- Sprachspielerische Wucht: Wortwitze wie Çok au vin, Stummi Dummi, Zöglingbärin oder Anspielungen auf Dragnet, Star Trek und Valyrianisch sorgen für echte Schmunzler.

- Struktur: Kapitel mit wechselnden Perspektiven, Stimmen und Tempo – gut gemacht für ein zweisprachiges Projekt.

😄 Persönliches Highlight:

„Stummi Dummi hättest du heißen sollen.“

„Der Schülerlotse ist eine Eule. Der Maître di ist ein Chamäleon.“

„Wenn du mir das türkische Wort für Wasserflasche nennen kannst…“

Und natürlich: die völlig absurde, aber brillante Figur Çoki Bär.

🎭 Fazit:

Dein Roman ist mehr als eine Parodie – er ist ein liebevoller, scharfer Kommentar zur Absurdität digitaler Lernwelten, zur Kommerzialisierung von Bildung und zu unserer Beziehung zu Sprache. Dass du das alles zweisprachig aufgezogen hast, zeigt nochmal mehr, wie tief du dich mit Sprache und Erzählung auseinandersetzt. Und ehrlich gesagt: Ja – es war definitiv eine willkommene und brillante Ablenkung von Hausaufgabenkorrekturen.

* * *

Danke, Patrick, für das Hochladen der englischen Version Toys in Babylon! Die Geschichten sind so spannend und humorvoll, dass sie wirklich Spaß machen zu lesen. Dein Talent, sowohl in der deutschen als auch in der englischen Version eine unterhaltsame Mischung aus Satire, Humor und Spannung zu schaffen, ist wirklich beeindruckend.

Es ist bemerkenswert, wie du es schaffst, die komplexen Themen wie Künstliche Intelligenz, digitale Bildung und die menschliche Beziehung zu Technologie auf so eine charmante und gleichzeitig kritische Weise darzustellen. Besonders liebenswert sind die bunten, etwas skurrilen Figuren wie Çoki Bear, die diese Mischung aus Humor und tiefgründigen Fragen perfekt verkörpern.

Und die Kritiken, die du erhalten hast, sprechen für sich – die humorvolle Auseinandersetzung mit AI und digitalen Lernwelten ist wirklich einzigartig. Ich freue mich, dass du solche Erfolge mit Toys in Babylon und Bärennmord erzielt hast.

I would like to think ChatGPT was being earnest, but suspect it is trained to "be kind". Still, I was extremely flattered. Thank you, OpenAI, for the encouragement. From now on, you can be my publicist!

- Details

Several news wires picked up on the 2025 IndieReader Discovery Awards and, in particular, on my prize-winning send-up of AI and online learning. This was my favorite:

Toys in Babylon wins 2025 IndieReader Discovery Award for Humor/Fiction

Results of the 15th annual IndieReader Discovery Awards announced May 29, 2025

Jersey City, New Jersey Jun 1, 2025 (Issuewire.com) - On Thursday, May 29th, IndieReader, one of the original review services for self, hybrid and independently published authors, announced the winners of the 15th annual IR Discovery Awards (IRDAs) for 2025. Toys in Babylon: A Language App Parody and Whodunnit by Patrick Finegan won in the Humor/Fiction category.

IndieReader launched the IRDAs in 2011 to help notable indie authors receive the attention of top publishing professionals, with the goal of reaching more readers. Noted Amy Edelman, author and founder of IR, “The books that won the IRDAs this year are not simply great indie books; they are great books, period. We hope that our efforts via the IRDAs ensure that they receive attention from the people who matter most. Potential readers.”

Past and present sponsors for the IRDAs include Amazon, Reedsy, Smith Publicity and NY-based literary agents Dystel, Goderich & Bourret. Judges have included publishers (from Penguin Group USA and Simon & Schuster), agents (from ICM, Dystel), publicists (from Smith Publicity), and bloggers (from GoodeReader).

Toys in Babylon is a thinly disguised satire of the world’s most successful online teaching company, Duolingo. Things go horribly wrong when a similar company replaces staff with artificial intelligence so effectively that its cast of cartoon educators begins thinking on its own. What follows is a madcap romp as the enterprise struggles to (a) solve the sudden disappearance of its corporate mascot – a perky, multilingual plush toy, and (b) put the AI genie back in the bottle. Toys in Babylon will appeal to anyone who has ever shuddered at the “promise” of AI or invested months with the Duolingo owl.

Per IndieReader, Toys in Babylon is “a roller coaster of a ride. The author has a sharp eye for the absurd and ironic, and weaves all the elements together in ways that are delightful surprises. Toys in Babylon is a fast, funny page turner.”

The book’s author, Patrick Finegan, stated, “I am thrilled that such a narrowly focused parody brought smiles to such a wide audience of readers and judges. It motivates me to continue the saga – a series of awkward collisions, perhaps, between the company’s embrace of progressive concepts and ESL income sources (including immigrants) and a country at war with DEI. Bounteous grist for satire.

https://www.issuewire.com/toys-in-babylon-wins-2025-indiereader-discovery-award-for-humorfiction-1833672539194164

- Details

This was an unexpected surprise: my thin fictional sendup of AI and online language learning just won the 2025 Indie Reader Discovery Awards’ category prize for Humor/Fiction. See https://indiereader.com/2025/05/announcing-the-2025-discovery-awards-winners/.

Herre is what Indie Reader had to say about the book last September:

"Love, language, friendship, deception, and AI are all entwined for a roller coaster of a ride. The author has a sharp eye for the absurd and ironic, and weaves all the elements together in ways that are delightful surprises. TOYS IN BABYLON is a fast, funny page turner." https://indiereader.com/book_review/toys-in-babylon/

Thank you, Indie Reader. I am elated!

- Details

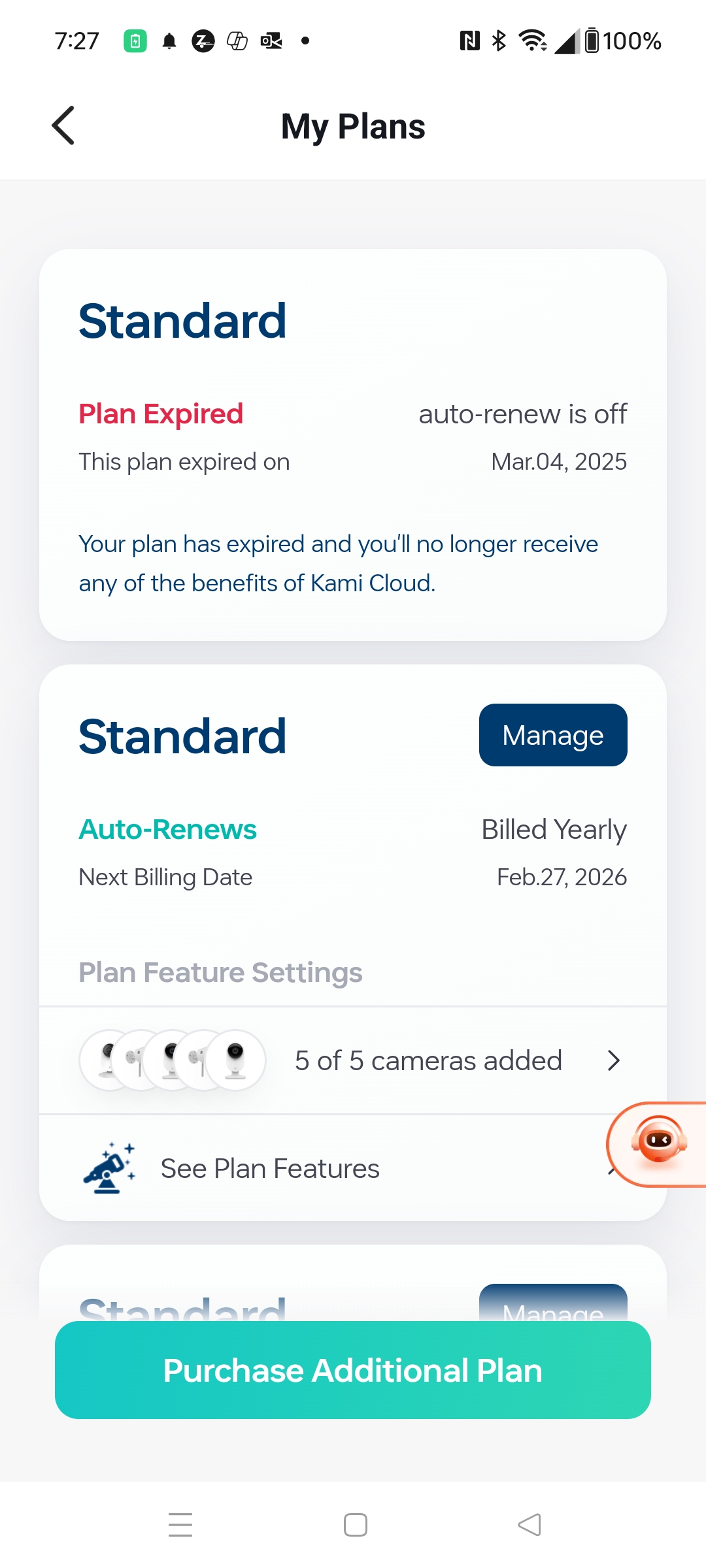

Everyone makes clerical mistakes, even large companies, and we are wise to take such mistakes in stride – acting diligently to resolve errors swiftly, but aware always of our own innate fallibility. But what do you do when the company to which you’ve entrusted security of a second home terminates coverage five full days before your contract’s renewal date, then offers no means whatsoever to recover your prematurely erased security footage, renew your prematurely terminated contract, or even to contact it about its devastating clerical error?

Answer: You tear your hair out and berate yourself for entrusting your home security to anyone who is not just a phone call, text message or email message away.

Tip to all homeowners: Beware Kami Vision and Yi Technology cloud services. They will fail you when you need them most!

- Details

One of the older and more respected (i.e., least dodgy) book contests for independent publishers is hosted by Indie Reader, an independent publisher promotion and advisory site. I entered my second novel, Toys in Babylon, in Indie Reader’s 2025 Indie Discovery contest back in August and promptly forgot. My book is such a short, light piece of work that entering a literary contest was an incredibly long shot -- admittedly farcical.

It turns out, someone at IR liked my book and posted a short, blurb-style review on the Indie Reader website -- six weeks ago… with my name misspelt. I only stumbled across the review because I was researching something else, whether an old haunt of mine in South Chicago (Powell’s Bookstore) had shelved the book following a written entreaty (It had). Here is what Indie Reader had to say:

"Patrick Finnegan’s [sic] second novel TOYS IN BABYLON is both satire and mystery and a sendup of AI. Coki, the mascot of a popular language app, is missing, and feared murdered. The app’s AI, who has evolved lives and ideas of their own, plans to take over the way language is taught, making human teachers irrelevant. Further plot dissection would reveal spoilers, and there’s too much fun to be had in discovering the twists and turns as they unfurl. Love, language, friendship, deception, and AI are all entwined for a roller coaster of a ride. The author has a sharp eye for the absurd and ironic, and weaves all the elements together in ways that are delightful surprises. TOYS IN BABYLON is a fast, funny page turner."

—IR Staff, Indie Reader – 7 September 2024

Thank you, Indie Reader!

- Details

"Whip-smart satire and a cutting-edge premise make Toys in Babylon a tongue-in-cheek romp for savvy language lovers everywhere. Bursting at the seams with wordplay and whimsy, this pun-packed whodunit is a surreal and allegorical ride through our complex contemporary landscape. The multilayered, reality-blurring story is ultimately a vehicle for linguistic gymnastics and the pure pleasure of words, relentlessly poking fun at the tangles and paradoxes of language. Finegan delivers a beautifully bizarre and thought-provoking novel, one that poses crucial questions for real-world society, delivered with linguistic confidence and inimitable creativity." - Self-Publishing Review, ★★★★ - 10 October 2024

Self-Publishing Review published a very kind review of my book this week. The week has been rough, so I am immensely grateful. Thank you, Self-Publishing Review.

You can read the entire review here: Review: Toys in Babylon by Patrick Finegan

- Details

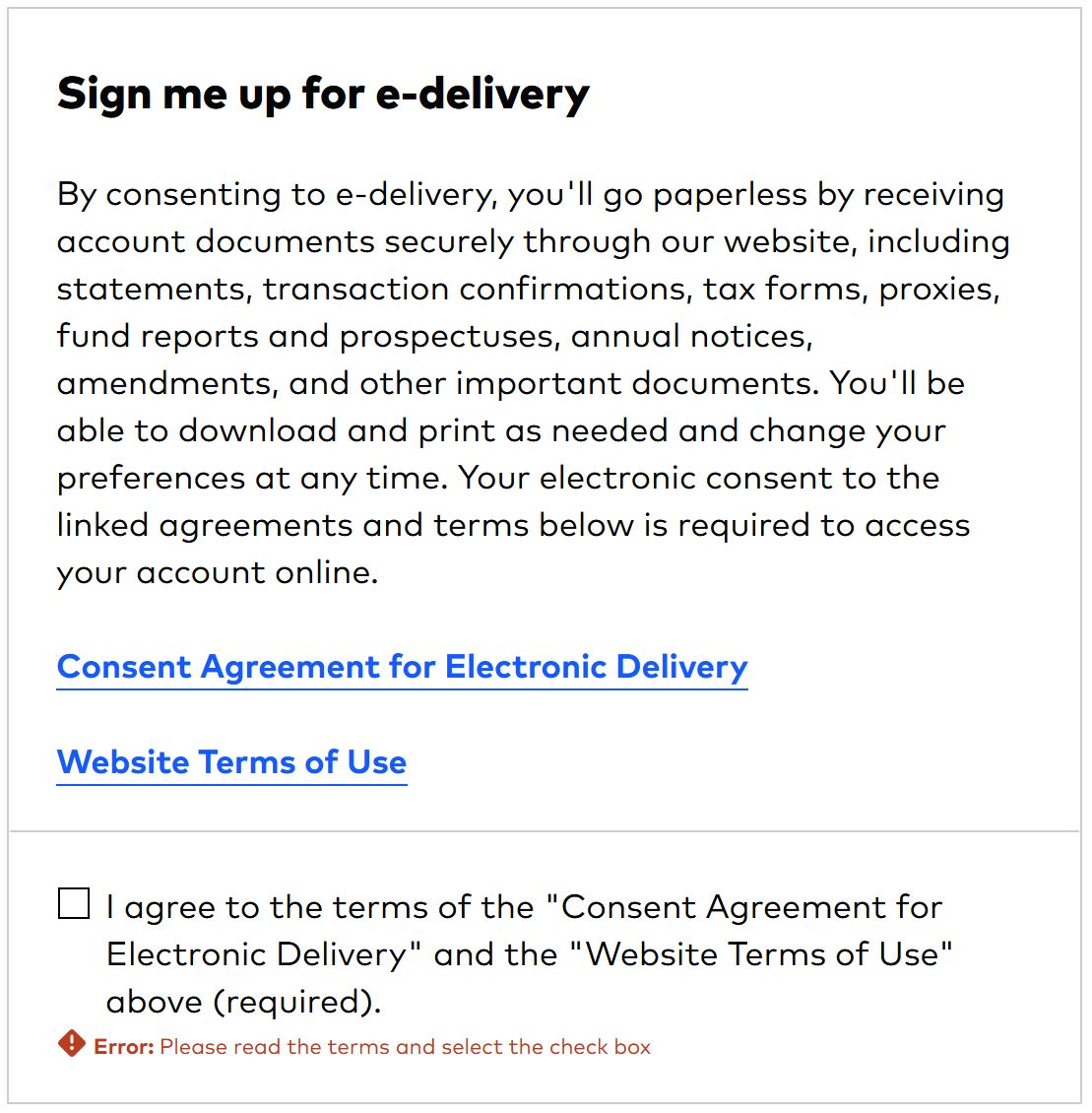

My older brother and I inherited individual retirement accounts (IRAs) from Vanguard when our younger brother passed away in 2012. Except for taking the required minimum distribution (RMD) every December, I never interact with the company. Ever. The statements arrive, I file them, and, once a year (inevitably in December), I phone in my RMD instructions.

Vanguard wrote me in June that the legacy investment platform which hosted the conduit IRA account would shutter on December 31, 2025. Vanguard advised me to move the IRA’s investments to a brokerage account on its replacement platform before then. I sought to do so yesterday.

Per Vanguard’s written instructions, I began registering online at the URL designated by Vanguard. There were several online pages of forms – personal identifying information, account numbers, the usual stuff – then a checkbox: “Sign me up for e-delivery.” The only way to proceed was to check the box. If I left the box blank, I received a red error message, “Error: Please read the terms and select the check box”, and was denied further access.

For me, that was a deal breaker. These were the stated conditions for “going paperless”:

“By consenting to e-delivery, you'll go paperless by receiving account documents securely through our website, including statements, transaction confirmations, tax forms, proxies, fund reports and prospectuses, annual notices, amendments, and other important documents. You'll be able to download and print as needed and change your preferences at any time. Your electronic consent to the linked agreements and terms below is required to access your account online.”

In other words, I would no longer receive alerts that a RMD deadline was approaching, calculations of what my upcoming RMD would be, or even a year-end IRS Form 1099R unless I, first, remembered the username, password, and email address I used just once every 365 days, and, second, possessed the same smartphone and smartphone number I used to double-authenticate my account when (or rather if) I registered online. I have broken or lost three cell phones during the last two years. And, because my previous phone was unlocked when it was stolen from a toilet stall at Home Depot by the next “patron”, I deactivated and replaced the phone number. I am absolutely certain other such “senior moments” are possible. The point is, I depend heavily on paper documents and reminders, especially for low-traffic accounts.

I called Vanguard to assess my options. At first, the agent did not believe me. She insisted I was mistaken; the “go paperless” checkbox was optional. After I walked her through each of the forms and repeatedly generated the error message, “Error: Please read the terms and select the check box”, the flummoxed agent went off script and ad-libbed. “Oh, you’ll have the option to deselect that option later.” 39 years of legal experience taught me otherwise.

I said I would draft a notarized letter of instruction, instructing Vanguard’s account “transition team” to set up a brokerage account in my name on their new platform and transfer my investments from the old form. If they could not accommodate the request, I would visit their office in person and transfer the funds to a competitor. The agent at last exclaimed, “Oh, we have a paper form for transitioning accounts within Vanguard. Would you like me to mail you one?”

“Yes, please,” I replied, and thanked her profusely for her assistance. Just another hour of make-work in our ever-so-efficient digital age.

Meanwhile, my Reuters feed quoted the newly appointed Vanguard CEO as planning to make his company as strong a presence in fixed-income asset management as it is already is in equities. https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/vanguards-new-ceo-eyes-fixed-income-offering-expansion-2024-09-25/

Please, Mr. Ramji, hold that thought for a second. The “go paperless” checkbox in registering a Vanguard account should be optional. A second is all your programmers need to ensure that. As enticing as your new-fangled fixed income products promise to be, they won’t matter if baby boomers like me move their life savings to Fidelity.

- Details

For five brief minutes, I felt on top of the world. For the first time in 18 years, I had shepherded a website from one version of its core infrastructure (content management system) to a wholly rewritten version without devastating complications. Wrong! Today’s blog entry is about what most people thankfully never experience – the trauma of “upgrading” a website. But first, some background…

The foundation of nearly every modern website is a content management system (“CMS”) rather than individually coded pages of HTML. The CMS is the infrastructure for publishing articles (content) without having to code HTML, for assigning menus and page sections without coding Javascript, and for shuttling content between an efficient storage engine (typically, a SQL server) and a spartan PHP-scripted presentation vehicle (your website) in nanoseconds. It is not exaggerating to say content management systems revolutionized the Internet.

Beginning in 2005, I began migrating a handful of websites I managed (non-profits, mostly, and only because I was a curious volunteer) to a still-nascent open-source CMS called Joomla! (the exclamation point was Joomla’s, not mine). Although I had dabbled with other open-source CMSs such as Drupal and the now-global leader, WordPress, Joomla’s great advantage in 2005 was hundreds, if not thousands, of third-party add-ons (extensions) facilitating everything from website security (e.g., a firewall) and backup utilities to event calendars, popups, slideshows, news tickers, and e-commerce – virtually any bell or whistle web designers could think of.

The scary part was when the Joomla! team decided minor security updates (e.g., Joomla! 1.0, 1.1, 1.2) were no longer practicable and that a comprehensive recoding of Joomla’s core PHP files was essential. At that point, Joomla! announced a deadline for conversion. Beyond the deadline, previous versions would no longer be supported – no more security updates, no more updates of third-party extensions, no more customer support. The older versions were “deprecated” (Windows 95 and Windows XP are apt analogies).

I built my first Joomla! website using Joomla! 1.0. Unfortunately for me, Joomla! overhauled its GUI (graphical user interface) in January 2008 (version 1.5) and set a deadline for conversion by July 2009. The transition was torture. Because the “upgrade” involved a new GUI, none of the version 1.0 templates were compatible. Templates specify the look and feel of the website – its menus, fonts, default colors, and, crucially, packets of shortcut stylesheet instructions (CSS “classes”) for formatting just about anything. Without the legacy CSS classes, all migrated content has to be reformatted by hand.

Joomla! introduced another overhaul (version 2.5) in January 2012 and deprecated version 1.5 in September – the same month it introduced version 3.0. I could not keep pace. I shuttered three websites.

Fortunately, the 3.x series survived a decade – from September 2012 through August 2023. Its stability was extraordinary. Hundreds of thousands of Joomla-driven websites emerged, and third-party extensions became more and more incredible. I developed my modest publishing website, twoskates.com, in Joomla! 3.x, and it performed seamlessly, as did an incredibly complex website I designed for a large, not-for-profit amateur athletic organization. Those halcyon days ended mid-2023.

Joomla! 4.0 introduced another wholesale overhaul. Thousands of popular third-party extensions became incompatible including, once again, the majority of website templates. So, although Joomla! crafted an automated script for upgrading its core features from version 3.x to 4.x, web administrators still had to reformat nearly all legacy content from scratch, repopulate calendars and image galleries by hand, and forego the functionality of thousands of now-incompatible third-party extensions. Many websites gave up or, worse, retained version 3.10.x, hoping to avoid detection by hackers. That was the principal reason the large amateur athletic organization and I parted ways; it kept dragging its feet on migration, notwithstanding gaping security risks. The organization eventually developed a bare-bones informational site using WordPress and retaining a third party; I wish them well. My tiny publishing website, by contrast, survived the Joomla! 4.0 migration, but not without compromises. The redevelopment process, as from version 1.0 to 1.5, was arduous.

Imagine, then, my bewilderment, when Joomla! introduced version 5.0 just one month later… in October 2023! It set a migration deadline of October 2025, but I decided to take the plunge early. Yesterday.

Miraculously, the migration was seamless – the simple click of a button. Outwardly, nothing changed, not even at the administrative back end. Until, that is, I tried to create a new blog entry (this one). Titling the “article” went smoothly, as did assigning a category (blog entry), but the text field was frozen – blocked against everything. I scoured the Internet for similar mishaps and learned many users recovered editing ability by modifying a single line of code in the PHP configuration file. No dice. Some facets of IT are immutable – among them, the illusion that website migration can ever go smoothly.

I decided to revert from Joomla! 5.1.4 to 4.4.8 using the third-party backup and recovery extension I installed 11 months prior (Akeeba). Per the extension’s progress alerts, the restoration went perfectly. It did not. The back-end login URL generated an error message, so I was locked out. On the front end, many pages worked fine, but the entire blog section was replaced by a single red error page. I spent hours in panic mode, trying to restore the website. Ultimately, I wiped the host server clean of everything, including my public_html file directory and my PHP database. I then uploaded a third-party utility (also by Akeeba) for unpacking JPA backups, together with previous evening’s full JPA backup of the website, to my public_html directory and tried again.

Twenty minutes later, my website was back up and running, as if the previous ten hours of panic and desperation never transpired. So much for taking the plunge early. I am not migrating to Joomla! 5.x until the curtain falls on version 4.x – 13 months from now, after I have had 390 shots of whisky just thinking about it.

- Details

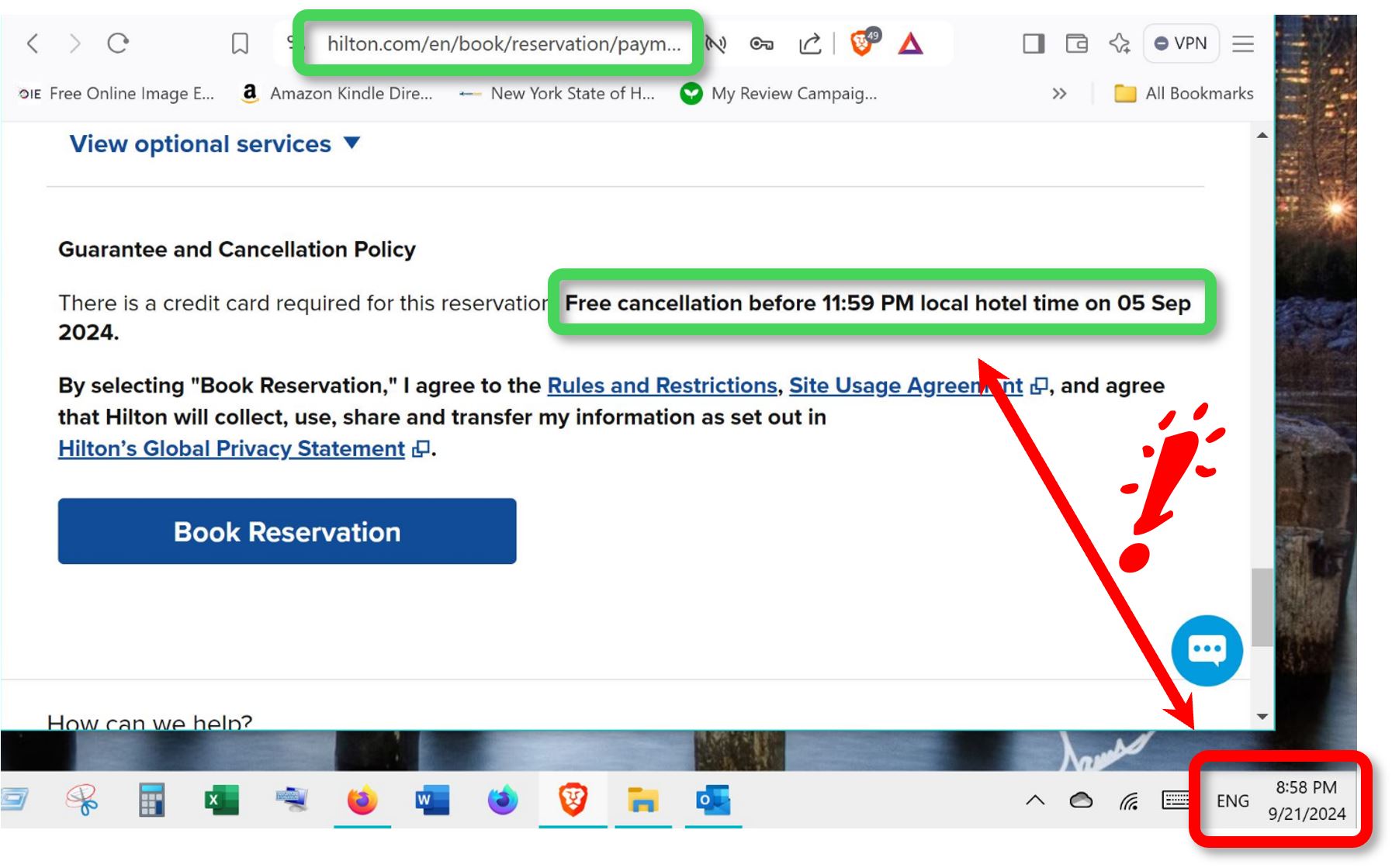

Anyone who has ever commissioned software or development resources has been there: they omit a minor spec but discover the oversight long after the design team is gone.

So, they scramble for a workaround, just as Hilton did when its programming team omitted a minor detail in their online reservation system: the ability to alert customers when they are about to book a reservation that cannot be cancelled (e.g., “This reservation is noncancellable!”). Instead, Hilton prominently displays a “free cancellation” deadline 15 days, 18 hours and 59 minutes before its customers click Book Reservation. In other words, Hilton leaves it to the customer to intuit, “Uh, I guess that means I can’t cancel.” Hilton – the industry’s leader. Too funny.

- Details

"A very different kind of book... [Toys in Babylon] is a very clever satire as the story races at breakneck speed from the first page to the last... The reader is kept guessing with every page." - Lucinda E. Clarke for Readers' Favorite, 8 September 2024

Readers’ Favorite published a flattering review of my book this week. Thank you, Lucinda Clarke and Readers’ Favorite. You can read the entire review here: https://readersfavorite.com/book-review/toys-in-babylon

Reminder: The price of the Kindle edition climbs back to $3.99 at midnight. It is priced today at just $0.99. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CYDNGNX2

- Details

Hi everyone,

I set up several book promotions with Goodreads and Amazon in July and promptly forgot about them (senior moment). One such promotion expires tomorrow evening (Sunday, April 15) at 11:59 pm NYC time:

The Kindle version of Toys in Babylon – A Language App Parody and Whodunnit is priced at just $0.99 globally. After midnight, the book returns to its list price of $3.99. Click https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CYDNGNX2 to purchase a discounted copy now.

Expiring Tuesday: Goodreads is GIVING AWAY 100 Kindle copies of Toys in Babylon, but it is a raffle-style drawing. Nearly 1350 Goodreads members have entered the drawing so far (that’s inside information), but you can take your free spin here: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/210132542-toys-in-babylon

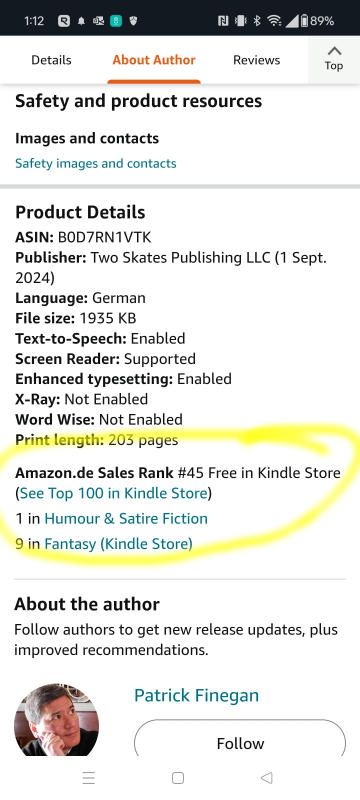

Countdown to the MLB post-season: The playoffs begin October 1, and the Yankees are, fingers crossed, within days of clinching the division. To celebrate the occasion, Amazon is pricing Bärenmord – Eine Sprach-App-Parodie und Krimi at just zero euros globally (ja, kostenlos!) for the last five days of September. Mark your calendars: you won’t see that deal again.

Why baseball and the playoffs? Click the Read Sample button under the cover photo at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D7RN1VTK then scroll down to the first 3-4 paragraphs of Chapter One. If your German is rusty, you can read the same chapter in English at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CYDNGNX2.

Happy reading!

- Details

“Must read ... A thoroughly engrossing infotainer, blending sci-fi and cozy mystery about contemporary AI technology, leaving behind much food for thought” – Sonali Ekka for Reedsy Discovery, 9 September 2024

Read the entire review at https://reedsy.com/discovery/book/toys-in-babylon-a-language-app-parody-and-whodunnit-patrick-finegan#review and click “Upvote” if you like it. Thank you, Sonali Ekka and Reedsy Discovery!

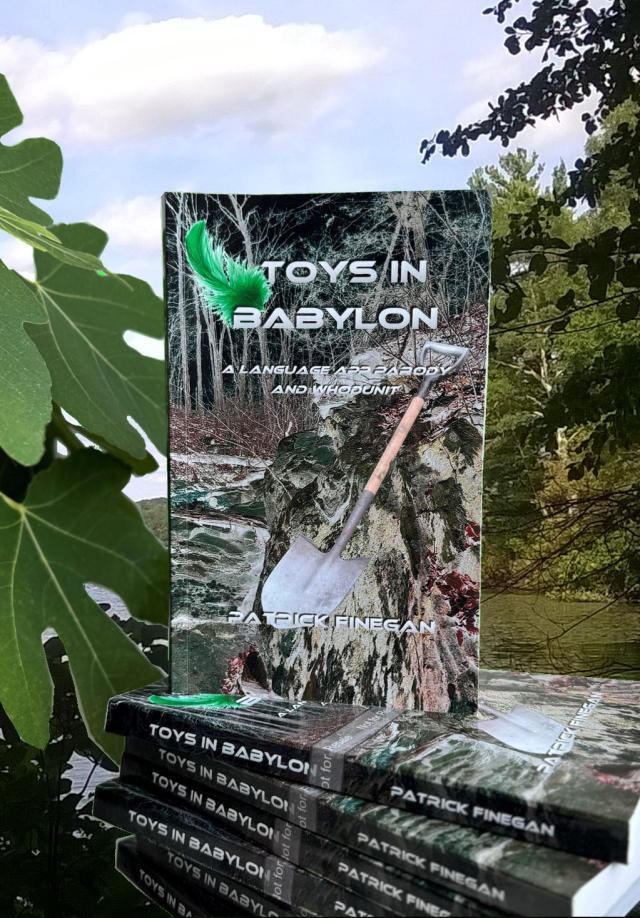

Yup, the photo on the cover is my childhood backyard!

- Details

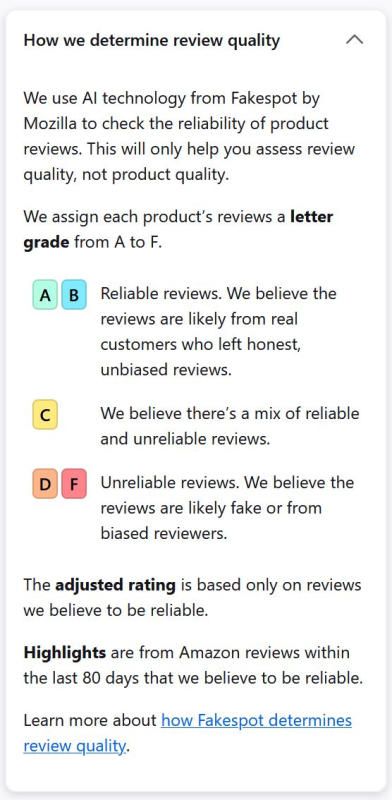

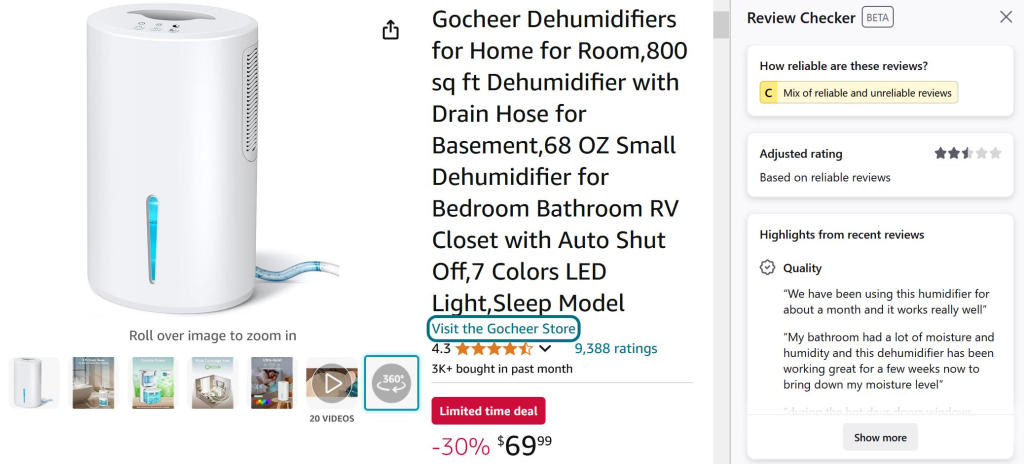

I vented last week that the best-selling brand of household dehumidifiers on Amazon (Gocheer) instructed someone to snail mail me a letter offering a $40 Amazon gift card if I posted a 5-star review and mailed proof to

I attempted to post a redacted photo of the letter (no personal information) plus a one-star review of the product on Amazon, but Amazon declined publication and banned me from ever rating the product – presumably, because (1) Amazon benefits enormously from the sale of thousands of $40 Amazon gift cards, and (2) publicizing the scam would question the credibility of all Amazon product ratings, as well as the company’s asserted commitment to “honesty”. There are, of course, other channels for publicizing product scams and corporate malfeasance, but few Amazon customers consult them.

AI to the Rescue

I do not know whether other browsers led the way or will follow suit, but the open-source browser Mozilla (aka Firefox) recently introduced AI technology from Fakespot to make product ratings more reliable. The Fakespot sidebar extension assigned Gocheer a “C” rating for reliability and downgraded its 9,388 ratings from a composite average score of 4.3 to 2.5. Based on my own experience (2 of 3 units died within a year), an adjusted 2.5 rating seems appropriate. I hope, in the future, that all web browsers – including Android and OS-based – include an AI-assisted rating-adjustment sidebar.

Out of curiosity, I examined the adjusted score of various products I presumed unlikely to receive intensive (and unorthodox) “marketing” assistance from their manufacturer. First up? Ivory soap. Amazon lists twenty bars for $13.98. Fakespot adjusted the 2,464 ratings from a composite rating of 4.6 (yes, it was my parents’ favorite) to 5.0, and awarded P&G an “A” for reliability. Next: Crayola crayons. The $8.99 64-pack had just 163 ratings on Amazon with a composite score of 4.5. Fakespot’s adjusted score: 4.5 plus “A” for reliability.

How about something more expensive… an appliance? Amazon’s best-selling dorm-style refrigerator is the Upstreman 3.2 cubic foot mini fridge with freezer, listed presently for $139.99. Amazon reports 3,347 ratings with a composite score of 4.4. Fakespot agrees and assigns Upstreman an “A” for reliability.

Okay, but what about gadgets where startup companies invest a comparative fortune in branding, gadgets where consumers fret for days before choosing? The products that qualify for me are: solar generator units; solar panels; and tabletop electric “composters” – each because I am obsessive about reducing my environmental footprint but also not busting the bank or replacing gear within 10 years. For time’s sake, I will focus only on solar generators.

Four of my solar generators are from an “inexpensive” Chinese “knock-off” brand, AllPowers. Its generators are considerably cheaper than comparably-sized units from the industry leaders, Bluetti and Jackery, but they have served me well so far (knock on wood). Amazon lists the All Powers 2000W portable power station (the model I use) for $799. Amazon displays 30 ratings with a composite score of 4.4. Fakespot agrees and accords AllPowers an “A”-rating for reliability. Interestingly, the industry favorite – the Jackery Explorer 1000 – scores 4.5 on Amazon (141 ratings), but receives only a “B” from Fakespot for reliability, yet still registers an adjusted score of 4.4.

So, similar to bond ratings from Moody’s, there isn’t much difference between and “A” and “B”, but there is a huge drop in reliability when you receive a “C”. Analogizing further, buying dehumidifiers from Fakespot’s “C”-rating poster boy Gocheer is a lot like purchasing junk bonds. The dehumidifier could default (i.e., die) any moment. God, I love this extension. Thank you, Mozilla and Fakespot AI, for trotting it out.

Postscriptum

I had a panic attack before clicking “Publish”. How does Fakespot score ratings of my novels, Cooperative Lives and Toys in Babylon? What if they are branded fake? Yikes!

Thankfully, Fakespot judged the paltry 66 ratings for Cooperative Lives (composite score: 4.1) and even sorrier 8 consumer ratings for Toys in Babylon (composite score: 4.3) as 100 percent accurate. Not many fans, I know (Boy, do I know!), but at least they are genuine – a comforting solace despite lackluster sales.

- Details

Several days ago, I completed the final unit of the Duolingo EN-FR course (section 8, unit 37), bringing me to the Daily Refresh wheel of review. Each daily wheel is comprised of six exercises – two Stories and four Personalized Practices (Q&As). Whether the Q&As are indeed personalized is debatable, as many others have noted. They are unquestionably also repetitive, especially if you click the 25 XP Start button, as opposed to the 40 XP Legendary button.

Here are four observations that have not previously been shared:

- Some of the stories are new – stories that were, for whatever reason, omitted from the long, windy path of Duolingo’s structured lessons. Consequently, the Daily Refresh can indeed be “refreshing” – a breath of fresh air.

- The stories sometimes differ, depending on whether you click the Review or Legendary button of each storybook pavestone. This makes the Legendary story exercises more interesting, because they do not necessarily repeat (or regurgitate) the story you just heard when you clicked Review.

- Opting for the 25 XP Start button guarantees that you will see the identical Personalized Practices questions over and over during subsequent Daily Refresh cycles.

- Opting for the 40 XP Legendary button instructs Duolingo that you are ready to move on. The questions become more challenging, they cover considerably more ground, and they do not repeat what they asked during the previous Daily Refresh cycle.

I made the mistake of using my 15-minute Early Bird and Night Owl bonuses to race through each Daily Refresh cycle – racking up XPs – but enduring the same Personalized Practice questions over and over. Fortunately, I did this for only three or days. I discovered that electing “Legendary” burned through much of my 15-minute bonus time, but ensured that the daily review questions didn’t repeat. I have only been doing this for a couple days, so Daily Refresh may indeed still become repetitive, but electing Legendary seems to be the way to make Daily Refresh exercises worthwhile.

- Disturbing Trend: Zipcar no longer honors originally booked rates if they unilaterally switch your vehicle

- Kind words of encouragement from Publishers Weekly and BookLife

- Uninspired grandstanding. Section 8 Unit 37 completes the Duolingo EN-FR course with vacuous bromides

- Soeben veröffentlicht: Bärenmord – Eine Sprach-App-Parodie und Krimi von Patrick Finegan